Published: 10 Aug 2011

Bloomberg | 10 August 2011Posted in: BlackRock | Ceres | George Soros | Jim Rogers | US

Perry Vieth, Co-Founder of Ceres Partners, stands in front of corn crops in Granger, Indian on June 22, 2011. (Photo: Roy Ritchie/Bloomberg)

By Seth Lubove

Perry Vieth baled hay on a neighbor’s farm in Wisconsin for two summers during high school in 1972 and 1973. The grueling labor left him with no doubt about getting a college degree so that he’d never have to work as hard again for a paycheck. Thirty-eight years later, and after a career as a securities lawyer and fixed-income trader, Vieth is back on the farm.

Except, now, he owns it. As co-founder of Ceres Partners LLC, a Granger, Indiana-based investment firm, Vieth oversees 61 farms valued at $63.3 million in Illinois, Indiana, Michigan and Tennessee. He’s so enthusiastic about the investments that he quit a job in 2008 overseeing $7 billion in fixed-income assets at PanAgora Asset Management Inc., a Boston-based quantitative money management firm, to focus full time on farming, Bloomberg Markets magazine reports in its September issue.

On a spring afternoon, Vieth, 54, barrels along backcountry roads in a Jeep Cherokee in Indiana and Michigan to scout a fruit orchard and corn and soybean farms to buy. Rural towns with names such as Three Rivers pass by in a blur, separated by a wide horizon of fields with young crops popping up.

“When I told people I was leaving to start an investment fund in farmland, they said, ‘You’re doing what?’” says Vieth, in a red polo golf shirt and khakis. “It will always be difficult for Wall Street firms to understand. It’s not like buying stocks on a computer.”

It’s much better: Returns from farmland have trounced those of equities. Ceres Partners produced an average annual gain of 16.4 percent after fees from January 2008, just after the firm started, through June of this year, Vieth says.

George Soros

The bulk of the returns are in rent payments from tenant farmers who grow and sell the crops and from land appreciation. The Standard & Poor’s GSCI Agriculture Index of eight raw materials gained 5.3 percent annually over the same period, and the S&P 500 Index (SPX) dropped almost 1 percent.

Investors are pouring into farmland in the U.S. and parts of Europe, Latin America and Africa as global food prices soar. A fund controlled by George Soros, the billionaire hedge-fund manager, owns 23.4 percent of South American farmland venture Adecoagro SA.

Hedge funds Ospraie Management LLC and Passport Capital LLC as well as Harvard University’s endowment are also betting on farming. TIAA-CREF, the $466 billion financial services giant, has $2 billion invested in some 600,000 acres (240,000 hectares) of farmland in Australia, Brazil and North America and wants to double the size of its investment.

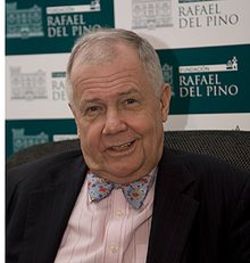

Jim Rogers

“I have frequently told people that one of the best investments in the world will be farmland,” says Jim Rogers, 68, chairman of Singapore-based Rogers Holdings, who predicted the start of the global commodities rally in 1996. “You’ve got to buy in a place where it rains, and you have to have a farmer who knows what he’s doing. If you can do that, you will make a double whammy because the crops are becoming more valuable.”

The growth in demand for food, spurred by the rising middle classes in China, India and other emerging markets, shows no signs of abating. Food prices in June, as measured by a United Nations index of 55 food commodities, were just slightly below their peak in February. The UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization said in a June report that it expects food costs to remain high through 2012.

So many investors have rushed to capitalize on food prices in the past three years that they may be creating a farmland bubble. The Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, which covers Colorado, Kansas, Nebraska and other agricultural states, said in May that farmland prices had surged 20 percent in the first quarter compared with a year earlier.

Safe Haven

“Yes, farmland will be a bubble again; all agricultural products will be in a bubble again,” says Rogers, who is an investor in Agrifirma Brazil Ltd., a South American farmland owner.

Hedge-fund manager Stephen Diggle calls farming the ultimate safe haven. Diggle began buying farms with his own money in 2008 after Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc. (LEHMQ) filed for bankruptcy in September of that year and the S&P 500 plunged 43 percent in the next six months. He purchased 8,000 acres in Uruguay, three smaller plots in southern Illinois and an 80-acre New Zealand kiwi-and-avocado orchard.

“We really thought all the investment banks would go under,” says Diggle, who as a hedge-fund manager uses options and warrants to bet on price swings in the market. “Everyone said, ‘Buy gold.’ But at the end of the day, you can’t eat it. If everything else goes and I just have these farms, it makes me moderately wealthy.”

‘Prosperous China’

The hedge fund Diggle co-founded, Artradis Fund Management Pte in Singapore, suffered about $700 million in losses. He closed it in March and opened another Singapore-based hedge fund, Vulpes Investment Management Pte. Diggle plans to incorporate his five farms into an investment management group run by Vulpes.

From his vantage point in Asia, where the British expatriate has worked for the past two decades, Diggle says he’s witnessed aspiring locals eating their way up the food chain.

“You can see what a more prosperous China will consume,” Diggle, 47, says. “It means more dairy, more meat -- not just pork and chicken.”

Investors find in farmland a respite from the cyclical price swings of the commodities market. Since 1970, there have been at least four price jumps of at least 100 percent that were followed by steep declines in the S&P agriculture commodities index. By contrast, the average value of an acre of farmland tracked by the U.S. Department of Agriculture has been on a mostly steady climb from $737 in 1980 to $2,350 in 2011.

Leaving BlackRock

“Farmland is the lowest-risk part of the value chain, but it’s also a key part of production,” says Jose Minaya, TIAA- CREF’s head of natural resources and infrastructure investments.

In the U.K., where farm prices are also rising, one money manager traded his career at BlackRock Inc. (BLK) for one in farming. Graham Birch, 51, left in 2009 as the London-based head of the natural resources team at BlackRock, the world’s biggest asset manager, to run his two dairy, wheat and barley farms in southwest England full time.

Birch, who says farming has suffered from a lack of investment and management talent, has spent $1 million on improvements. He now captures all of the effluent from his 600- cow herd, stores it in a 4 million-liter (1-million-gallon) steel tank and uses it as fertilizer for his crops. “At heart, I am basically a businessman, and I want to try to apply the things I learned over the years to see what I could do,” Birch says.

Wall Street Roots

Ceres Partners’ Wall Street roots are evident in the firm’s makeshift office in an old clapboard farmhouse that sits in the middle of cropland. Lucite tombstones resting on a shelf in a small room mark deals done by Brandon Zick, a former vice president of strategic acquisitions at Morgan Stanley (MS)’s investment management unit. Vieth hired Zick in January to help analyze and manage farm purchases.

Vieth, a 1982 graduate of the University of Notre Dame Law School, began his career as a securities and corporate lawyer before moving to the pits of the Chicago Mercantile Exchange, where he traded S&P 500 options. After a series of stints running an arbitrage team for Fuji Securities Inc. and other firms, he was hired as chief investment officer of fixed income at PanAgora, the quant firm, in 1999.

By about 2006, Vieth’s concerns about the economy were mounting: Inflation was at a low, and the dollar had peaked as U.S. debt and deficits soared. So he searched for an asset class that would benefit from a currency decline and rising prices. His research led him to farms, since a falling dollar boosts U.S. crop exports.

Falling Dollar

Vieth then connected with Paul Blum, a fellow Notre Dame alumnus who spent some of his youth on a farm in upstate New York and today acts as Ceres’s point person with tenant farmers.

As the dollar fell 24 percent against the euro from January 2006 through May 2008, the pair started buying land as personal investments until the business grew too big for Vieth to manage during evenings and weekends. So, in late 2007, he founded Ceres, just as tightening credit markets began to push the global economy into a recession.

He named the firm Ceres for both the Roman goddess of agriculture and a bar he frequented during his trading days in Chicago. “I was more convinced hard assets were where you wanted to be, and farmland was the best investment I could identify,” Vieth says. By May 2011, he had collected 17,238 acres, mostly in the Midwest.

Shade and Rocks

When Vieth wants land, he goes shopping, as he does with Zick and Blum under a partly cloudy southern Michigan sky in May. Armed with aerial and soil maps, they look for farms with predictable rainfall, mineral-rich land and good drainage. They avoid land that slopes too much, which could lead to soil erosion.

The trio drive by a 337-acre farm for sale by a bank, and Vieth frowns at the slant of the land and the trees that line the perimeter. “Those trees will shade the corn and stunt growth,” he says. Blum doesn’t like the many rocks scattered on the unplanted dirt. Zick is skeptical that the bank will get its asking price of $7,000 an acre in a foreclosure sale.

The investors next visit a farmer they hired, Ed Kerlikowske Jr., who grows watermelon, peas and corn on their 782-acre spread near Berrien Springs, Michigan. For farmers such as Kerlikowske, the entry of outside investors frees up money for new equipment that they would otherwise have to spend on land. “To really grow the business in today’s economy, you need partners,” Kerlikowske says as he passes around slices of fresh watermelon.

Possible Bubble

The farm-investing boom is making lots of people happy, but could it all end in tears? The Federal Deposit Insurance Corp., which regulates banks that lend to farmers, has examined whether investors may be pumping up prices and creating the conditions for a crash like the one that devastated the market in the 1980s, resulting in the failure of 300 farm banks.

In March, then-FDIC Chairman Sheila Bair devoted a symposium to the topic in Washington with the participation of economists, bankers and agricultural experts. “If there is a bubble in farmland prices, I hope the bulk of any correction is borne by investors such as hedge funds and not by the banking industry,” William Isaac, chairman of the FDIC during the farm banking bust and now senior managing director of FTI Consulting Inc. (FCN) said during the event.

Overpaying

Charles McNairy, whose family has been involved in agriculture since 1871, says neophyte investors who lack a deep understanding of farming are making bad deals. In 2009, McNairy started U.S. Farming Realty Trust LP, a fund based in Kinston, North Carolina, that had raised $261 million as of late May to buy farms, according to a Securities and Exchange Commission filing.

McNairy says funds such as Ceres have been overpaying for land, based on the return from crops. “Ceres shouldn’t be buying in the Midwest,” says McNairy, who declined to disclose the states he invests in. “It’s crazy to be buying up there.”

Vieth disagrees, saying Ceres’s returns prove that his strategy is working. “I certainly don’t want to start slinging mud, but I don’t know what the heck he’s talking about.”

Greyson Colvin, who started farming fund Colvin & Co. LLP in Anoka, Minnesota, in 2009, dismisses the idea of an overheated market. “After the housing bubble, people are a little too quick to assign the word bubble these days,” says Colvin, whose two funds and separately managed accounts hold 2,300 acres of farmland in Iowa, Minnesota and South Dakota valued at more than $10 million.

Head Winds

Colvin, a former analyst at UBS AG (UBSN) and Credit Suisse Group AG (CSGN), says U.S. farmers aren’t carrying as much debt as they did during the 1980s crisis, which contributed to the downfall of banks as agriculture loans defaulted. The farm debt-to-asset ratio, which peaked in 1985 at 23 percent, is expected to fall to 10.7 percent in 2011, according to Agriculture Department estimates.

Vieth’s farm funds are facing head winds in coming months and years: A likely rise in interest rates will push up his acquisition costs and the value of the dollar, which in turn might hurt commodity exports. While the former trader keeps a close eye on the dollar, he says farming will continue to thrive.

Investors seem to agree. At a dining-room table in the farmhouse in Granger, Vieth sits down at his computer one evening and totals the day’s haul: another $900,000 from investors looking for comfort -- and profits -- in one of the oldest and most essential industries on the planet.

To contact the reporter on this story: Seth Lubove in Los Angeles at slubove@bloomberg.net;

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Laura Colby in New York at lcolby@bloomberg.net.

Source: Bloomberg

Council on Hemispheric Affairs | August 8, 2011

A land-grabber’s loophole

This analysis was prepared by COHA Research Associates Paula Lopez-Gamundi & Winston Hanks

• Due to the global food crisis, a trend has developed in food-insecure countries to outsource food production to lesser developed countries.

• Current stipulations regulating the purchase of farmland by foreigners can be undermined by renting land.

• Exemplifying this trend, the Río Negro-Beidahuang agreement was signed without the consent of the indigenous residents of the region and may threaten the environment.

• Latin American governments should focus on developing sustainable food programs for their own populations; this will include protecting the inherent territorial rights of their indigenous groups and safeguarding their environment.

The acuteness of the global food crisis has forced overpopulated and arid countries, such as China, India, Saudi Arabia and Egypt to desperately scour the globe, looking for land on which to cultivate their staple crops. In an effort to secure food sources and financial returns, food insecure governments are increasingly outsourcing their food production to more fertile and usually less-developed countries, including Pakistan, Uganda, Argentina and Brazil. While some of these land-selling states have welcomed the foreign revenue, others have begun to rightfully resist these “agrifood” agreements.

The MERCOSUR (Mercado Común del Sur) countries of Argentina, Uruguay, and Brazil have decided to regulate foreign powers’ ability to purchase large tracts of land. In response to these mild initiatives, various foreign corporations have begun to set up negotiations to rent, rather than purchase, arable land from less-developed countries, treating land usage rights as merely one more commodity.

Case Study: Argentina

Exemplifying the leasing trend, the Chinese food corporation Heilogjiang Beidahuang State Faros Business Trade Group Co., Ltd. made arrangements with the provincial government of Río Negro, Argentina to rent large tracts of land for the production of genetically modified staple crops for exportation to China. Protected by their own governments, these agrifood leases may be quickly becoming the face of neocolonialism in Latin America.

The Details

The contract between Beidahuang and the government of Río Negro was signed in October of 2010, yet was made public, in English and Chinese, only in early 2011. Behind closed doors, the governor of the Patagonian province, Miguel Saiz, agreed to lease out a total of 320,000 hectares (ha) of land to the Chinese company over the course of twenty years for the production of genetically modified (GM) soy, corn, wheat, barley, and sunflowers [1].

At first glance, the Beidahuang-Río Negro agreement seems equitable—the Chinese pay USD 1.45 billion to the government of Río Negro and, in turn, win the right to build a badly-needed irrigation system to secure a food source for the next 20 years [2]. However, excessive tax exemptions, environmental hazards, lack of legislative restrictions, and continued neglect of Río Negro’s indigenous population demonstrate ways in which the agreement inevitably will favor the Chinese corporation.

The Beidahuang-Río Negro business deal grants generous tax exemptions and handouts that end up pampering the Chinese company. Excused from having to pay provincial income taxes, patent fees, and other charges on aspects such as gross revenues and stamps, Beidahuang Food Company is also exempt from having to adhere to the national standard of “reserve requirements” [2]. The contract even requires the people of Río Negro to provide free office space and discounted housing, transportation and office equipment for Chinese workers and engineers. Additionally, the Argentine province is required to reserve five ha of land for the construction of exclusive Beidahuang port facilities, allowing the Chinese investors to have access to parts of Río Negro’s San Antonio Este port, free of charge, until the new harbor is complete [3].

All together, these overwhelming handouts and tax exemptions bias the agreement in favor of the Chinese company and, in turn, diminish Río Negro’s economic power. Furthermore, Saiz is allowing Beidahuang to bring its own hydro engineers to design the USD 20 million irrigation system [4]. The use of Chinese engineers and the highly mechanized nature of soya cultivation would predictably create a small number of jobs for Argentines living in the region.

Environment Under Attack

Patagonia is infamous for its dry and arid climate, which is home to expansive cattle grazing. While grazing alone significantly alters the environment, the introduction of a Chinese-designed irrigation system and the use of genetically modified seeds have justifiably angered residents. Chinese irrigation practices are notably problematic, as almost 40 percent of China’s total land is plagued by soil erosion [5]. Worried that these practices will be transferred to the Río Negro valley, environmentalists and concerned citizens have begun to protest.

Leading the resistance, Nobel Prize winner and president of the Environment Defense Foundation (FUNAM), Dr. Raúl Montenegro, has accused the government of Río Negro of violating the Ley Provincial de Impacto Ambiental n° 3266 and the Ley Nacional del Ambiente n° 25675 — national and provincial laws requiring transparency and studies on the environmental impact of new projects [6]. Taking their complaints to the courts, a group of 24 concerned citizens from Viedma (a city in Río Negro) presented their case to Supreme Court Judge Sodero Nievas, on June 26, 2011. The plaintiffs demand a halt to the Beidahuang agrifood project due to the agreement’s violation of the Río Negro constitution and the high potential for water contamination through the use of genetically modified soy, corn, and other cereal seeds [7].

The Viedma plaintiffs, amongst other groups such as the Asociación Biológica del Comahue, the Grupo de Reflección Rural, the Asamblea de Vecinos y Organizaciones del Alto Valle Movilizados por la Soberanía Alementaria and numerous university students, are concerned that the toxins in genetically modified seeds—products long held to be detrimental to one’s health—may contaminate the water, affecting livestock as well as humans. While the effects of genetically modified (GM) seeds are contested, there is a large body of scientific evidence indicating that long-term exposure to GM soy and corn can weaken defenses against cancer and heart disease, increase allergic reactions, and reduce fertility in men [8][9][10][11]. Since the agrifood contract trial period only tests yields and not environmental effects, it seems that the people in the Río Negro region will be serving as human guinea pigs, potentially sacrificing their health to provide a secure food source for the Chinese.

The Continued Marginalization of the Mapuche

Work will continue as planned and in August, the Chinese company is scheduled to begin sowing in the middle and lower Río Negro Valleys, that serve as the traditional home of the indigenous Mapuche people. The provincial government leased these lands to the Chinese corporation without ever consulting the true owners of the land—the Mapuche.

Not surprisingly, the Beidahuang-Río Negro agreement was met with immediate uproar and public rejection from the Consejo Asesor Indígena (CAI), Viedma and the Mapuche people. Existing legislation requires the government to specifically acknowledge and respect indigenous peoples and their land rights. Amendments enacted to article 75(22) of the Argentine constitution in August 1994 mandate the government to guarantee respect for cultural identity and to recognize and secure all indigenous peoples’ rights to land [12][13]. Furthermore, in 2006, the Argentine government ratified the International Labour Organization (ILO) Convention No. 169, thereby incorporating the global standard of indigenous peoples’ rights into Argentine law (Law 24.071). Currently, the Mapuche people are considering taking legal action to halt the Beidahuang project on the basis that the provincial government never asked for informed consent prior to signing the agreement—a right that is guaranteed in Law 24.071 [14].

The recent agreement between the provincial government of Río Negro and Beidahuang is simply one example of territorial abuse against the indigenous peoples of Argentina. The state carries out development plans on indigenously owned land without consultation, causing displacements, evictions, expropriations, harassment, and permanent discontent [15]. Federal courts have historically protected violations of constitutional article 75(22), as in the case of a forced eviction of families of the Quilmes Indigenous Community this June in the northern province of Tucumán [16][17]. With no way to seek reparations or rectitude from the national government, the indigenous people of Argentina are left with no defenses to fend off neo-colonial menaces that wish to sequester their land.

Simply put, the Argentine government has taken a hypocritical stance in respecting the indigenous in their country. On one hand, it cordially tips its hat to the international community by incorporating international laws and codes protecting indigenous rights; on the other hand, the Argentine government routinely infringes upon the territorial rights of its indigenous peoples, thereby breeding domestic discontent.

Legislation to the Rescue?

Current Argentine laws do not limit foreign ownership of land in any way, shape, or form. On April 27, 2011, President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner submitted a bill to the Argentine Congress “For the Protection of the National Dominion Over Rural Land.” The proposal caps foreign ownership of land to 20 percent of Argentina’s 40 million hectares of rural land. In addition, persons or companies from foreign countries are limited to owning up to 1,000 hectares of land, equivalent to 6 percent of the allotted land designated for foreigners. Moreover, foreigners are required to report details of their land ownership to an Inter-ministerial Board of Rural Property [18].

However, the proposed bill leaves many issues, such as workers’ rights, environmental protection, and indigenous territorial rights, unaddressed. The bill lacks clarity in its clauses about national oversight and definition of ‘foreigners’ or a ‘foreign company’. One clause labels a company as foreign once 51 percent of the company’s capital stock is in the hands of foreigners, while the second requires only 25 percent [19][20]. A further limitation is that if implemented, the bill would not be applied retroactively, thereby excluding the Beidahuang-Río Negro contract from any reforms. The challenges associated with this bill will involve not only drafting and passing an effective bill, but abiding by its rules once it passes—something the Argentine government has failed to do with existing legislation dealing with indigenous lands. The establishment of a regulatory committee mandated to oversee the details of any private land agreement, similar to the U.S. Government Accountability Office, would allow for stricter adherence to environmental and human rights norms. This committee could establish trial periods for land sale agreements to monitor the environmental effects on lands sold and investigate the effects of such agreements on the environment and the indigenous inhabiting the area.

Respect Thy Neighbor

Though Paraguay, Uruguay, and Bolivia are also experiencing their own land-grab phenomena, a large portion of their business partners are not from overseas. Drawn by cheaper land and reduced exportation taxes, Argentina and Brazil are buying adjacent lands from their neighbors in order to build up their respective soy empires.

In Paraguay, Argentine firms and individuals own about 60 percent of the 3 million hectares of land used to cultivate soy. Furthermore, as of 2010, foreigners own 19.4 percent (7,889,128 ha) of all Paraguayan land. Uruguay’s status is equally eye-opening: Argentines own almost all of the 500,000 ha of Uruguayan soil designated for soy cultivation, while foreigners own a total of 5.5 million ha of territory, or 25 percent of the country’s total arable land [21]. This unsettling trend continues in Bolivia, where foreign agribusiness investors own or rent over one million ha of the nation’s land: Brazilian investors claim 700,000 ha; the Argentine’s, 100,000 ha; Middle Easterners and Japanese, 200,000 ha. Due to the threat of agrarian reform, it is possible that many of these agribusiness transactions are not even publicly registered, leaving many lands unaccounted for by the Bolivian government [22].

Initiatives to slow the transfer of land to foreigners have proved futile thus far. Paraguay ratified the toothless Law 2.532/5 in 2005, which prohibits the sale of land to foreigners, except those from neighboring countries in areas within 50 kilometers of the border [23]. Furthermore, after 15 years of agrarian reform, Bolivia has yet to restrict the “foreignization” of land through any legislative means.

Uruguay has also shown limited promise in establishing restrictive legislation. Uruguayan Senator Jorge Saravia publicly announced his plans to submit a report to the current president, José Mujica, concerning the sale of land to foreigners [24]. Although former Frente Amplio President Tabaré Vázquez failed to rally support for a bill that restricted the transfer of lands to foreigners, the Frente Amplio (Broad Front) coalition’s current domination of the Uruguayan Assembly sustains hope for the initiative’s eventual success. No current or past legislation in the region discusses restrictions for leasing land.

The Looming Prevalence of Land-Grab Loopholes

Restrictive legislation on the selling of land will continue to be null and void so long as foreigners can rent farm land. Regardless of any progress in creating legislation against the transfer of lands to foreigners, all efforts may be undermined by a Beidahuang-like contract, or the ‘leasing loophole’.

Unfortunately, Argentina is not the only country in the neighborhood that has back-tracked by utilizing the lease loophole. As one of the world’s largest agriculture exporters, Brazil has interest in protecting its agriculture sector from foreign speculation. Last year, the attorney general’s office began to enforce the Brazilian real estate law to restrict and oversee foreign land grabbing. Prompted by 2010’s USD 15 billion loss of foreign direct investment, Brazilian president Dilma Rousseff is desperately looking for ways to relax restrictions on foreign investment. Rousseff and her agriculture minister, Wagner Rossi, are contemplating leasing land out to foreign companies to circumvent the current restrictive legislation against the purchase of land, thus ushering in a new era of neo-colonialism [25].

Food for Thought

The heads of indigenous people and innocent citizens of underdeveloped regions, such as the Río Negro, oftentimes comprise the steps to the stairway of economic success. While the Beidahuang-Río Negro agreement will provide China with a source of sustenance for the next 20 years, Argentina’s soil fertility and national sovereignty will suffer. Without strong legislation that restricts the quantity of land available to foreigners, without regulations that protect the integrity of their land and water sources and without institutionalized representation of indigenous interests, Latin American countries may quickly fall down the slippery slope of foreign speculation and domination.

The redirection of food markets is particularly urgent for countries such as Bolivia, where 23 percent of the population is listed as undernourished by the Human Development Index [26]. Understandably, these MERCOSUR countries want to lure new investors, but their governments should also invest in the domestic agricultural sector to spur food production for local markets. Initiatives to increase production on domestic farms should come from the state itself. The Alliance Against Hunger and Malnutrition has suggested that agro-ecological initiatives improve domestic crop production by significantly reducing rural poverty, protecting farmers from the volatility of prices on the world market, and cutting out state subsidies on foods in local markets [27]. Essentially, the governments of these countries should teach domestic farmers new advanced techniques and allow for fair competition in order to promote self-sufficiency.

Until they can secure food for their own populations, countries such as Paraguay, Bolivia, Uruguay, and Argentina should strive for sustainable agrifood agreements that stimulate job creation and benefit, rather than harm, their own people. Instead of allowing their lands to be exploited by multinational corporations, these Latin American countries must wean themselves off foreign demands and make their own food security their top priority.

References

1. “Chinos empezarán con trigo en Río Negro,” Río Negro Diario, accessed May 12, 2011, http://www.rionegro.com.ar/diario/rn/nota.aspx?idart=628126&idcat=9545&tipo=2.

2. “New Agricultural Agreement in Argentina: A Land-Grabber’s ‘Instruction Manual’,” Against the Grain, accessed June 5, 2011, http://www.grain.org/articles/?id=77

3. “Consideraciones Generales,” Convenio de Cooperación para la presentación de una propuesta de inversión para la instalación de una nueva terminal portuaria en la area del Puerto de San Antonio Este, accessed June 27, 2011.

4. Ibid.

5. “40% of China’s territory suffers from soil erosion,” Xinhua News Agency, accessed June 28, 2011, http://www.china.org.cn/environment/news/2008-11/21/content_16803229.htm.

6. “Soja: Río Negro y China hacen acuerdo illegal,” No a La Mina, accessed July 5, 2011, http://www.noalamina.org/mineria-informacion-general/general/soja-rio-negro-y-china-hacen-acuerdo-ilegal.

7. “Presentan amparo contra los convenio con la empresa china,” Río Negro- Costa y Línea Sur, accessed June 28, 2011, http://www.rionegro.com.ar/diario/rn/nota.aspx?idart=649933&idcat=9545&tipo=2.

8. C.M. Webb, C. S. Hayward, M. J. Mason, C. D. Ilsley, P. Collins, “Coronary vasomotor and blood flow responses to isoflavone-intact soya protein in subjects with coronary heart disease or risk factors for coronary heart disease,” Clinical Science (London), 115(12), 353-359.

9. Daniel R. Doerge and Daniel M. Sheehan, “Goitrogenic and Estrogenic Activity of Soy Isoflavones,” Environmental Health Perspectives (110), 349-353.

10. K. Hirsch, A. Atsmon, M. Danilenko, J. Levy, Y. Sharoni, “Lycopene and other cartenoids inhibit estrogenic activity of 17beta-estradiol and genistein in cancer cells,” Brest Cancer Res Treat 104(2), 221-230.

11. “Austrian Government Study Confirms Genetically Modified (GM) Crops Threaten Human Fertility and Health Safety,” Institute for Responsible Technology, accessed June 28, 2011, http://www.prisonplanet.com/austrian-government-study-confirms-genetically-modified-gm-crops-threaten-human-fertility-and-health-safety.html.

12. "More Information on the Argentine Constitution of 1994," Columbia Law School, accessed June 20, 2011, .

13. Dr. Abduallah A. Faruque, "Constitutional Recognition of Indigenous People," The Daily Star, accessed June 18, 2011, .

14. Ibid. Against the Grain.

15. Maria Delia Bueno, “Indigenous Rights in Argentina,” Canadian Foundation for the Americas, accessed July 5,2011, http://www.focal.ca/publications/focalpoint/413-march-2011-maria-delia-bueno-en.

16. “Segunda Parte: Autoridades de la Nación; Capítulo Cuarto Atribuciones del Congreso,” Honorable Senado de la Nación, accessed July 22, 2011, http://www.senado.gov.ar/web/interes/constitucion/atribuciones.php.

17. "Quilmes Indigenous Community Facing Third Eviction in Three Years," Intercontinental Cry, accessed July 1, 2011, .

18. Miguel Menegazzo Cané, “Potential Restriction on the Acquisition of Rural Land by Foreign Parties,” Buenos Aires Office—Baker & Mckenzie, accessed June 10, 2011,

http://www.bakermckenzie.com/files/Publication/88f5bb4b-195e-4784-b3df-c73f9cdcb653/Presentation/PublicationAttachment/25b56848-e100-4eee-a3eb-c760fdaff8aa/ar_buenosaires_potentialrestrictionsruralland_apr11.pdf.

19. Ibid, Miguel Menegazzo Cané.

20. Negri & Teijeiro Abogados, “Argentina Seeks to Cap Rural Land Ownership by Foreigners,” accessed June 28, 2011.

21. “Mas de un millón de hectáreas en manos de extranjeros,” Bolpress, accessed June 14, 2011, http://www.bolpress.com/art.php?Cod=2011032817.

22. Miguel Urioste, Concentración y extranjerización de la tierra en Bolivia, (La Paz: Fundación TIERRA), 37.

23. Marcos Glauser, Extranjerización del territorio paraguayo, (Asunción: BASE Investigaciones Sociales), 34.

24. “Este año debatiremos sobre la extranjerización de la tierra,” Food Crisis and the Global Land Grab, accessed June 28, 2011, http://farmlandgrab.org/post/view/18208.

25. “Brazil considering leasing farm land to foreigners to circumvent sales restrictions, Merco Press, accessed June 12, 2011, http://en.mercopress.com/2011/05/10/brazil-considering-leasing-farm-land-to-foreigners-to-circumvent-sales-restrictions.

26. Country Profiles of Human Development Indicators: Bolivia (Plurinational State of),” United Nations Development Program, accessed July 6, 2011, http://hdr.undp.org/en/.

27. Oliver De Schutter, “Report submitted by the Special Raporteur on the right to food,” Human Rights Council- Sixteenth Session, (United Nations) 19.

Quantum co-founder bullish on commodities

Published: 10 Aug 2011

Posted in: Jim Rogers

Top1000Funds.com | August 10, 2011

Quantum co-founder bullish on commodities

by SAM RILEY

As stock markets continued to be volatile and bears abounded, Jim Rogers, the co-founder with George Soros of the Quantum hedge fund, was one of few bullish voices. Rogers said that commodities will defy a stuttering world economy and depressed financial markets to enjoy a 20-year bull run.

Rogers, who launched the Quantum fund with Soros in 1973, said the tumultuous market conditions of recent days reminded him of the investment environment of the 1970s.

One of the world’s most famous hedge funds, Quantum is credited with making its private investors about 20 per cent every year since its inception.

“I am long on commodities, I remember in the 1970s when economies around the world were in trouble, commodities had one of the great bull runs in history,” Rogers said.

“I am long commodities, many are far depressed from their all-time historical highs, so I would prefer to be long commodities, as in the 1970s, and short stocks.”

With the exception of the safe haven of gold, commodity prices in recent days have broadly fallen on the back of pessimistic outlooks for global economic growth.

In July the world’s biggest commodities trader, Glencore, also reported a pullback demand from China as the government attempted to slow the economy and domestic commodity buyers ran down inventories.

Rogers says he is not worried by short-term uncertainties, and said he sees long-term shortages in commodities combined with higher inflation as making for attractive opportunities.

“In the 1970s we had serious shortages and we had money printing, and a huge bull market in commodities with bad economies,” Rogers said.

“In the ’70s, stocks did nothing but commodities went through the roof. That was my investment then and I have invested the same way again.”

Declining financial markets would also exacerbate shortages in commodities, with less productive capacity being added in the coming years, Rogers said.

Rogers quit Quantum to “retire” in the 1980s and rode a motorbike across China. He later sold his New York property and relocated his family to Singapore.

In the late 1990s, Rogers launched his own commodities index products.

His Rogers International Commodities Index (RICI) claims it has made 303.31 per cent since launching in the late 1990s but has lost more than 5 per cent in the year to date.

In the total index, the biggest holdings are crude oil (21 per cent), brent oil (14 per cent), wheat (4.75 per cent), corn (4.75 per cent), and cotton (4.20 per cent).

The index is comprised of 38 different commodities and Rogers said he invests his own money into the indexes.

In its investment information, the RICI claims it decides on what commodities to include in the index by examining a commodity’s overall liquidity and world consumption patterns.

It sets its basket of commodities annually through a management committee that includes representatives from UBS, Merrill Lynch and The Royal Bank of Scotland.

Rogers was in Australia recently to promote his indexes to retail investors through the Royal Bank of Scotland.

Investors gain access to the index through Exchange Traded Certificates that are listed securities on the Australian Securities Commission.

Rogers is particularly bullish about agriculture saying that shortages in a range of agricultural products will produce strong prices not only in those commodities but also in farm land.

“Farmland is going to be one of the great investments of the next 10 to 20 years. First of all, agriculture is going to be one of the most exciting investment markets because agriculture prices are down, inventories are down to historic lows and we have a shortage of farmers.”

“The average age of farmers in the US and in Australia is 58, in Japan it is 66, we have serious shortages facing us in the world and prices have to go much higher for agricultural products and, therefore, agricultural land.”

Rogers was also scathing in his analysis of hedge fund of funds, saying he didn’t believe the business model made for a good investment.

“I can see no reason why hedge fund of funds exist, it is just an extra layer of leverage, an extra layer of fees and an extra layer of expense, I can see no justification at all,” he said.

While unprepared to comment on the recent news that George Soros was closing his Quantum Fund to outside investors and returning all external money, Rogers said increased regulatory requirements would make it hard for hedge funds to enjoy the same success.

“It is going to be more difficult in finance in the next few years than it was in the past, finance is not a popular area anymore,” he said.

“You should become a farmer instead of a hedge fund manager if you want to get rich. Farming is going to be one of the great businesses of our time. Learn how to drive a tractor or you could be driving a taxi.”

Quantum co-founder bullish on commodities

by SAM RILEY

As stock markets continued to be volatile and bears abounded, Jim Rogers, the co-founder with George Soros of the Quantum hedge fund, was one of few bullish voices. Rogers said that commodities will defy a stuttering world economy and depressed financial markets to enjoy a 20-year bull run.

Rogers, who launched the Quantum fund with Soros in 1973, said the tumultuous market conditions of recent days reminded him of the investment environment of the 1970s.

One of the world’s most famous hedge funds, Quantum is credited with making its private investors about 20 per cent every year since its inception.

“I am long on commodities, I remember in the 1970s when economies around the world were in trouble, commodities had one of the great bull runs in history,” Rogers said.

“I am long commodities, many are far depressed from their all-time historical highs, so I would prefer to be long commodities, as in the 1970s, and short stocks.”

With the exception of the safe haven of gold, commodity prices in recent days have broadly fallen on the back of pessimistic outlooks for global economic growth.

In July the world’s biggest commodities trader, Glencore, also reported a pullback demand from China as the government attempted to slow the economy and domestic commodity buyers ran down inventories.

Rogers says he is not worried by short-term uncertainties, and said he sees long-term shortages in commodities combined with higher inflation as making for attractive opportunities.

“In the 1970s we had serious shortages and we had money printing, and a huge bull market in commodities with bad economies,” Rogers said.

“In the ’70s, stocks did nothing but commodities went through the roof. That was my investment then and I have invested the same way again.”

Declining financial markets would also exacerbate shortages in commodities, with less productive capacity being added in the coming years, Rogers said.

Rogers quit Quantum to “retire” in the 1980s and rode a motorbike across China. He later sold his New York property and relocated his family to Singapore.

In the late 1990s, Rogers launched his own commodities index products.

His Rogers International Commodities Index (RICI) claims it has made 303.31 per cent since launching in the late 1990s but has lost more than 5 per cent in the year to date.

In the total index, the biggest holdings are crude oil (21 per cent), brent oil (14 per cent), wheat (4.75 per cent), corn (4.75 per cent), and cotton (4.20 per cent).

The index is comprised of 38 different commodities and Rogers said he invests his own money into the indexes.

In its investment information, the RICI claims it decides on what commodities to include in the index by examining a commodity’s overall liquidity and world consumption patterns.

It sets its basket of commodities annually through a management committee that includes representatives from UBS, Merrill Lynch and The Royal Bank of Scotland.

Rogers was in Australia recently to promote his indexes to retail investors through the Royal Bank of Scotland.

Investors gain access to the index through Exchange Traded Certificates that are listed securities on the Australian Securities Commission.

Rogers is particularly bullish about agriculture saying that shortages in a range of agricultural products will produce strong prices not only in those commodities but also in farm land.

“Farmland is going to be one of the great investments of the next 10 to 20 years. First of all, agriculture is going to be one of the most exciting investment markets because agriculture prices are down, inventories are down to historic lows and we have a shortage of farmers.”

“The average age of farmers in the US and in Australia is 58, in Japan it is 66, we have serious shortages facing us in the world and prices have to go much higher for agricultural products and, therefore, agricultural land.”

Rogers was also scathing in his analysis of hedge fund of funds, saying he didn’t believe the business model made for a good investment.

“I can see no reason why hedge fund of funds exist, it is just an extra layer of leverage, an extra layer of fees and an extra layer of expense, I can see no justification at all,” he said.

While unprepared to comment on the recent news that George Soros was closing his Quantum Fund to outside investors and returning all external money, Rogers said increased regulatory requirements would make it hard for hedge funds to enjoy the same success.

“It is going to be more difficult in finance in the next few years than it was in the past, finance is not a popular area anymore,” he said.

“You should become a farmer instead of a hedge fund manager if you want to get rich. Farming is going to be one of the great businesses of our time. Learn how to drive a tractor or you could be driving a taxi.”

Source: Top1000Funds

How would an investor export maize or rice from a famine-hit country? Published: 08 Aug 2011 |

Posted in: African Agriculture | August 08, 2011 How would an investor export maize or rice from a famine-hit country? by Chido Makunike The controversies over foreign investment in African land continue to rage. From the many issues heatedly raised will hopefully emerge models of investment that achieve the aims of the various parties without being seen as exploitative. It is and will continue to be a huge challenge for all concerned, but foreign investment in African agriculture is neither new nor will the factors driving both investors and host countries to consider it diminish in the near term. The first modern Africa land rush was when European countries carved up the continent into the economic spheres of influence that correspond to Africa's borders today. A key part of the colonization process that followed involved the introduction of 'cash crops' like coffee, cotton, groundnuts and many others on huge estates to supply the raw materials for the colonial metropole's industrial processes. Sometimes long after some of these crops have ceased to be economically viable, many African countries' economies still heavily depend on them, creating all sorts of problems that have so far defied easy solution. Together with the introduction of new crops and farming techniques, that first wave of land 'investment' also involved conquest, large-scale dispossession and relocation, forced labor and many of the other lingering effects that today cause many Africans to be instinctively suspicious of modern-day investors. In theory the self-governing status of today's African countries should protect against the abuses of the colonial era but this is far from straight-forward and certain to skeptics. So finding a model that works to maximize the hoped-for benefits for investors and locals while minimizing the many issues of concern is clearly an on-going process. The drought and famine in East Africa is already throwing up some uncomfortable questions for the model of large scale agro-investment in a poor country for export. How would an agribusiness be able to export maize from a famine-stricken country that depends on the crop as its staple food? The furore over South Korean company Daewoo's plans to grow export maize in Madagascar was at least in a mainly rice-eating country. But imagine an investor had spent years and millions of dollars developing export-maize plantations in a mainly maize-eating east African country amidst the region's current famine. How would it look for the investor to cite 'but that's what we agreed' as a reason to export the maize in the face of mass local maize starvation? More to the point, regardless of the investment agreement signed, would the government dare to allow such exports in a time of famine? Easy, some might say, the investor should take this into account by incorporating a special 'famine' escape clause into his contract with his export markets, explaining that in the event of a local shortage he would not be able to supply, and would have to sell the maize locally. But is this as clear cut as that may sound? Because of of the fraught, political importance of maize in Africa, it is not really a fully freely-tradeable crop, especially in times of scarcity. In the midst of a maize famine in which the government has prohibited exports but also does not have money to pay for your maize, what happens? In a 'free market' situation you should be able to keep the maize in your warehouse until you have negotiated a satisfactory payment arrangement, but how realistic is that in a time of famine? What about if the government issues an emergency decree setting the maize purchase price below the investor's cost of production? This is far from a mere rhetorical question: in many countries this has often been a reality. The government needs to keep maize prices high enough to encourage farmers, but also low enough to keep this highly political crop at prices 'affordable' to the voters. Government price subsidies are sometimes part of the mix of answers but they are expensive and hard to sustain. Price ceilings whose considerations are as much political as economic/agricultural are sometimes another part of the answer, especially in difficult times. If the government commandeers all the country's production of the staple crop by requiring all of a season's maize production to be sold to the government-owned maize marketing monopoly (not unheard of), promising to pay when it can, how does the investor pay his debts in the meantime? This is a problem that has plagued African commercial maize farmers in almost every country at one time or another. Of course the investor may hope he is given special dispensation in the event of any of these matters arising, which could be the case, but in a famine all bets are off. So the investor looks at all this and says, ''Okay, I will avoid growing locally 'political' crops for export in case these issues come up. I will grow something more safe, lucrative and non-political, like flowers.'' The investor buys or leases huge parcels of land to grow flowers for export. All seems to go very well for some time. Everyone is pleased at the new jobs, revenue, etc. When drought hits, the investor's hands are 'clean' because he doesn't have to get involved in the inevitably messy supply/price politics of staple crops during times of shortage. But then the drought persists and there are growing concerns that your export flowers are using up too much of the water that should go for other more pressing concerns. You immediately point to the appropriate clause in your investment contract promising you X millions of liters of water for Y number of years. But if a government is forced to choose between honoring the promises it made to an investor in a 'normal' time and the needs/demands of hungry, angry hordes during a time of famine, well... Africa needs all kinds of investment in its agriculture; that much everybody seems to agree on. The potential negatives of the current waves of large-scale investments have mainly been examined from the perspectives of how the host countries have not done enough to ensure a fair deal for themselves. But as the few examples presented here try to show, there are also investors who will get burned not because the idea of investing itself was wrong, but because they were naive, over-eager and failed to do sufficient due diligence before deciding how, where and in what specific sectors to invest in. All you investors who are sure you 'know Africa,' if and when your carefully laid business plan goes belly up during a famine, don't say you weren't warned at the beginning about the many not so-obvious factors to ponder. Related reading: Africa increasingly questions the sustainability of dependence on maize for food security Source: African Agriculture |

A land-grabber’s loophole

Published: 08 Aug 2011

The provincial government leased lands to the Chinese corporation without ever consulting the true owners of the land—the Mapuche. Photo source: http://www.rn24.com.ar

A land-grabber’s loophole

This analysis was prepared by COHA Research Associates Paula Lopez-Gamundi & Winston Hanks

• Due to the global food crisis, a trend has developed in food-insecure countries to outsource food production to lesser developed countries.

• Current stipulations regulating the purchase of farmland by foreigners can be undermined by renting land.

• Exemplifying this trend, the Río Negro-Beidahuang agreement was signed without the consent of the indigenous residents of the region and may threaten the environment.

• Latin American governments should focus on developing sustainable food programs for their own populations; this will include protecting the inherent territorial rights of their indigenous groups and safeguarding their environment.

The acuteness of the global food crisis has forced overpopulated and arid countries, such as China, India, Saudi Arabia and Egypt to desperately scour the globe, looking for land on which to cultivate their staple crops. In an effort to secure food sources and financial returns, food insecure governments are increasingly outsourcing their food production to more fertile and usually less-developed countries, including Pakistan, Uganda, Argentina and Brazil. While some of these land-selling states have welcomed the foreign revenue, others have begun to rightfully resist these “agrifood” agreements.

The MERCOSUR (Mercado Común del Sur) countries of Argentina, Uruguay, and Brazil have decided to regulate foreign powers’ ability to purchase large tracts of land. In response to these mild initiatives, various foreign corporations have begun to set up negotiations to rent, rather than purchase, arable land from less-developed countries, treating land usage rights as merely one more commodity.

Case Study: Argentina

Exemplifying the leasing trend, the Chinese food corporation Heilogjiang Beidahuang State Faros Business Trade Group Co., Ltd. made arrangements with the provincial government of Río Negro, Argentina to rent large tracts of land for the production of genetically modified staple crops for exportation to China. Protected by their own governments, these agrifood leases may be quickly becoming the face of neocolonialism in Latin America.

The Details

The contract between Beidahuang and the government of Río Negro was signed in October of 2010, yet was made public, in English and Chinese, only in early 2011. Behind closed doors, the governor of the Patagonian province, Miguel Saiz, agreed to lease out a total of 320,000 hectares (ha) of land to the Chinese company over the course of twenty years for the production of genetically modified (GM) soy, corn, wheat, barley, and sunflowers [1].

At first glance, the Beidahuang-Río Negro agreement seems equitable—the Chinese pay USD 1.45 billion to the government of Río Negro and, in turn, win the right to build a badly-needed irrigation system to secure a food source for the next 20 years [2]. However, excessive tax exemptions, environmental hazards, lack of legislative restrictions, and continued neglect of Río Negro’s indigenous population demonstrate ways in which the agreement inevitably will favor the Chinese corporation.

The Beidahuang-Río Negro business deal grants generous tax exemptions and handouts that end up pampering the Chinese company. Excused from having to pay provincial income taxes, patent fees, and other charges on aspects such as gross revenues and stamps, Beidahuang Food Company is also exempt from having to adhere to the national standard of “reserve requirements” [2]. The contract even requires the people of Río Negro to provide free office space and discounted housing, transportation and office equipment for Chinese workers and engineers. Additionally, the Argentine province is required to reserve five ha of land for the construction of exclusive Beidahuang port facilities, allowing the Chinese investors to have access to parts of Río Negro’s San Antonio Este port, free of charge, until the new harbor is complete [3].

All together, these overwhelming handouts and tax exemptions bias the agreement in favor of the Chinese company and, in turn, diminish Río Negro’s economic power. Furthermore, Saiz is allowing Beidahuang to bring its own hydro engineers to design the USD 20 million irrigation system [4]. The use of Chinese engineers and the highly mechanized nature of soya cultivation would predictably create a small number of jobs for Argentines living in the region.

Environment Under Attack

Patagonia is infamous for its dry and arid climate, which is home to expansive cattle grazing. While grazing alone significantly alters the environment, the introduction of a Chinese-designed irrigation system and the use of genetically modified seeds have justifiably angered residents. Chinese irrigation practices are notably problematic, as almost 40 percent of China’s total land is plagued by soil erosion [5]. Worried that these practices will be transferred to the Río Negro valley, environmentalists and concerned citizens have begun to protest.

Leading the resistance, Nobel Prize winner and president of the Environment Defense Foundation (FUNAM), Dr. Raúl Montenegro, has accused the government of Río Negro of violating the Ley Provincial de Impacto Ambiental n° 3266 and the Ley Nacional del Ambiente n° 25675 — national and provincial laws requiring transparency and studies on the environmental impact of new projects [6]. Taking their complaints to the courts, a group of 24 concerned citizens from Viedma (a city in Río Negro) presented their case to Supreme Court Judge Sodero Nievas, on June 26, 2011. The plaintiffs demand a halt to the Beidahuang agrifood project due to the agreement’s violation of the Río Negro constitution and the high potential for water contamination through the use of genetically modified soy, corn, and other cereal seeds [7].

The Viedma plaintiffs, amongst other groups such as the Asociación Biológica del Comahue, the Grupo de Reflección Rural, the Asamblea de Vecinos y Organizaciones del Alto Valle Movilizados por la Soberanía Alementaria and numerous university students, are concerned that the toxins in genetically modified seeds—products long held to be detrimental to one’s health—may contaminate the water, affecting livestock as well as humans. While the effects of genetically modified (GM) seeds are contested, there is a large body of scientific evidence indicating that long-term exposure to GM soy and corn can weaken defenses against cancer and heart disease, increase allergic reactions, and reduce fertility in men [8][9][10][11]. Since the agrifood contract trial period only tests yields and not environmental effects, it seems that the people in the Río Negro region will be serving as human guinea pigs, potentially sacrificing their health to provide a secure food source for the Chinese.

The Continued Marginalization of the Mapuche

Work will continue as planned and in August, the Chinese company is scheduled to begin sowing in the middle and lower Río Negro Valleys, that serve as the traditional home of the indigenous Mapuche people. The provincial government leased these lands to the Chinese corporation without ever consulting the true owners of the land—the Mapuche.

Not surprisingly, the Beidahuang-Río Negro agreement was met with immediate uproar and public rejection from the Consejo Asesor Indígena (CAI), Viedma and the Mapuche people. Existing legislation requires the government to specifically acknowledge and respect indigenous peoples and their land rights. Amendments enacted to article 75(22) of the Argentine constitution in August 1994 mandate the government to guarantee respect for cultural identity and to recognize and secure all indigenous peoples’ rights to land [12][13]. Furthermore, in 2006, the Argentine government ratified the International Labour Organization (ILO) Convention No. 169, thereby incorporating the global standard of indigenous peoples’ rights into Argentine law (Law 24.071). Currently, the Mapuche people are considering taking legal action to halt the Beidahuang project on the basis that the provincial government never asked for informed consent prior to signing the agreement—a right that is guaranteed in Law 24.071 [14].

The recent agreement between the provincial government of Río Negro and Beidahuang is simply one example of territorial abuse against the indigenous peoples of Argentina. The state carries out development plans on indigenously owned land without consultation, causing displacements, evictions, expropriations, harassment, and permanent discontent [15]. Federal courts have historically protected violations of constitutional article 75(22), as in the case of a forced eviction of families of the Quilmes Indigenous Community this June in the northern province of Tucumán [16][17]. With no way to seek reparations or rectitude from the national government, the indigenous people of Argentina are left with no defenses to fend off neo-colonial menaces that wish to sequester their land.

Simply put, the Argentine government has taken a hypocritical stance in respecting the indigenous in their country. On one hand, it cordially tips its hat to the international community by incorporating international laws and codes protecting indigenous rights; on the other hand, the Argentine government routinely infringes upon the territorial rights of its indigenous peoples, thereby breeding domestic discontent.

Legislation to the Rescue?

Current Argentine laws do not limit foreign ownership of land in any way, shape, or form. On April 27, 2011, President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner submitted a bill to the Argentine Congress “For the Protection of the National Dominion Over Rural Land.” The proposal caps foreign ownership of land to 20 percent of Argentina’s 40 million hectares of rural land. In addition, persons or companies from foreign countries are limited to owning up to 1,000 hectares of land, equivalent to 6 percent of the allotted land designated for foreigners. Moreover, foreigners are required to report details of their land ownership to an Inter-ministerial Board of Rural Property [18].

However, the proposed bill leaves many issues, such as workers’ rights, environmental protection, and indigenous territorial rights, unaddressed. The bill lacks clarity in its clauses about national oversight and definition of ‘foreigners’ or a ‘foreign company’. One clause labels a company as foreign once 51 percent of the company’s capital stock is in the hands of foreigners, while the second requires only 25 percent [19][20]. A further limitation is that if implemented, the bill would not be applied retroactively, thereby excluding the Beidahuang-Río Negro contract from any reforms. The challenges associated with this bill will involve not only drafting and passing an effective bill, but abiding by its rules once it passes—something the Argentine government has failed to do with existing legislation dealing with indigenous lands. The establishment of a regulatory committee mandated to oversee the details of any private land agreement, similar to the U.S. Government Accountability Office, would allow for stricter adherence to environmental and human rights norms. This committee could establish trial periods for land sale agreements to monitor the environmental effects on lands sold and investigate the effects of such agreements on the environment and the indigenous inhabiting the area.

Respect Thy Neighbor

Though Paraguay, Uruguay, and Bolivia are also experiencing their own land-grab phenomena, a large portion of their business partners are not from overseas. Drawn by cheaper land and reduced exportation taxes, Argentina and Brazil are buying adjacent lands from their neighbors in order to build up their respective soy empires.

In Paraguay, Argentine firms and individuals own about 60 percent of the 3 million hectares of land used to cultivate soy. Furthermore, as of 2010, foreigners own 19.4 percent (7,889,128 ha) of all Paraguayan land. Uruguay’s status is equally eye-opening: Argentines own almost all of the 500,000 ha of Uruguayan soil designated for soy cultivation, while foreigners own a total of 5.5 million ha of territory, or 25 percent of the country’s total arable land [21]. This unsettling trend continues in Bolivia, where foreign agribusiness investors own or rent over one million ha of the nation’s land: Brazilian investors claim 700,000 ha; the Argentine’s, 100,000 ha; Middle Easterners and Japanese, 200,000 ha. Due to the threat of agrarian reform, it is possible that many of these agribusiness transactions are not even publicly registered, leaving many lands unaccounted for by the Bolivian government [22].

Initiatives to slow the transfer of land to foreigners have proved futile thus far. Paraguay ratified the toothless Law 2.532/5 in 2005, which prohibits the sale of land to foreigners, except those from neighboring countries in areas within 50 kilometers of the border [23]. Furthermore, after 15 years of agrarian reform, Bolivia has yet to restrict the “foreignization” of land through any legislative means.

Uruguay has also shown limited promise in establishing restrictive legislation. Uruguayan Senator Jorge Saravia publicly announced his plans to submit a report to the current president, José Mujica, concerning the sale of land to foreigners [24]. Although former Frente Amplio President Tabaré Vázquez failed to rally support for a bill that restricted the transfer of lands to foreigners, the Frente Amplio (Broad Front) coalition’s current domination of the Uruguayan Assembly sustains hope for the initiative’s eventual success. No current or past legislation in the region discusses restrictions for leasing land.

The Looming Prevalence of Land-Grab Loopholes

Restrictive legislation on the selling of land will continue to be null and void so long as foreigners can rent farm land. Regardless of any progress in creating legislation against the transfer of lands to foreigners, all efforts may be undermined by a Beidahuang-like contract, or the ‘leasing loophole’.

Unfortunately, Argentina is not the only country in the neighborhood that has back-tracked by utilizing the lease loophole. As one of the world’s largest agriculture exporters, Brazil has interest in protecting its agriculture sector from foreign speculation. Last year, the attorney general’s office began to enforce the Brazilian real estate law to restrict and oversee foreign land grabbing. Prompted by 2010’s USD 15 billion loss of foreign direct investment, Brazilian president Dilma Rousseff is desperately looking for ways to relax restrictions on foreign investment. Rousseff and her agriculture minister, Wagner Rossi, are contemplating leasing land out to foreign companies to circumvent the current restrictive legislation against the purchase of land, thus ushering in a new era of neo-colonialism [25].

Food for Thought

The heads of indigenous people and innocent citizens of underdeveloped regions, such as the Río Negro, oftentimes comprise the steps to the stairway of economic success. While the Beidahuang-Río Negro agreement will provide China with a source of sustenance for the next 20 years, Argentina’s soil fertility and national sovereignty will suffer. Without strong legislation that restricts the quantity of land available to foreigners, without regulations that protect the integrity of their land and water sources and without institutionalized representation of indigenous interests, Latin American countries may quickly fall down the slippery slope of foreign speculation and domination.

The redirection of food markets is particularly urgent for countries such as Bolivia, where 23 percent of the population is listed as undernourished by the Human Development Index [26]. Understandably, these MERCOSUR countries want to lure new investors, but their governments should also invest in the domestic agricultural sector to spur food production for local markets. Initiatives to increase production on domestic farms should come from the state itself. The Alliance Against Hunger and Malnutrition has suggested that agro-ecological initiatives improve domestic crop production by significantly reducing rural poverty, protecting farmers from the volatility of prices on the world market, and cutting out state subsidies on foods in local markets [27]. Essentially, the governments of these countries should teach domestic farmers new advanced techniques and allow for fair competition in order to promote self-sufficiency.

Until they can secure food for their own populations, countries such as Paraguay, Bolivia, Uruguay, and Argentina should strive for sustainable agrifood agreements that stimulate job creation and benefit, rather than harm, their own people. Instead of allowing their lands to be exploited by multinational corporations, these Latin American countries must wean themselves off foreign demands and make their own food security their top priority.

References

1. “Chinos empezarán con trigo en Río Negro,” Río Negro Diario, accessed May 12, 2011, http://www.rionegro.com.ar/diario/rn/nota.aspx?idart=628126&idcat=9545&tipo=2.

2. “New Agricultural Agreement in Argentina: A Land-Grabber’s ‘Instruction Manual’,” Against the Grain, accessed June 5, 2011, http://www.grain.org/articles/?id=77

3. “Consideraciones Generales,” Convenio de Cooperación para la presentación de una propuesta de inversión para la instalación de una nueva terminal portuaria en la area del Puerto de San Antonio Este, accessed June 27, 2011.

4. Ibid.

5. “40% of China’s territory suffers from soil erosion,” Xinhua News Agency, accessed June 28, 2011, http://www.china.org.cn/environment/news/2008-11/21/content_16803229.htm.

6. “Soja: Río Negro y China hacen acuerdo illegal,” No a La Mina, accessed July 5, 2011, http://www.noalamina.org/mineria-informacion-general/general/soja-rio-negro-y-china-hacen-acuerdo-ilegal.

7. “Presentan amparo contra los convenio con la empresa china,” Río Negro- Costa y Línea Sur, accessed June 28, 2011, http://www.rionegro.com.ar/diario/rn/nota.aspx?idart=649933&idcat=9545&tipo=2.

8. C.M. Webb, C. S. Hayward, M. J. Mason, C. D. Ilsley, P. Collins, “Coronary vasomotor and blood flow responses to isoflavone-intact soya protein in subjects with coronary heart disease or risk factors for coronary heart disease,” Clinical Science (London), 115(12), 353-359.

9. Daniel R. Doerge and Daniel M. Sheehan, “Goitrogenic and Estrogenic Activity of Soy Isoflavones,” Environmental Health Perspectives (110), 349-353.

10. K. Hirsch, A. Atsmon, M. Danilenko, J. Levy, Y. Sharoni, “Lycopene and other cartenoids inhibit estrogenic activity of 17beta-estradiol and genistein in cancer cells,” Brest Cancer Res Treat 104(2), 221-230.

11. “Austrian Government Study Confirms Genetically Modified (GM) Crops Threaten Human Fertility and Health Safety,” Institute for Responsible Technology, accessed June 28, 2011, http://www.prisonplanet.com/austrian-government-study-confirms-genetically-modified-gm-crops-threaten-human-fertility-and-health-safety.html.

12. "More Information on the Argentine Constitution of 1994," Columbia Law School, accessed June 20, 2011, .

13. Dr. Abduallah A. Faruque, "Constitutional Recognition of Indigenous People," The Daily Star, accessed June 18, 2011, .

14. Ibid. Against the Grain.

15. Maria Delia Bueno, “Indigenous Rights in Argentina,” Canadian Foundation for the Americas, accessed July 5,2011, http://www.focal.ca/publications/focalpoint/413-march-2011-maria-delia-bueno-en.

16. “Segunda Parte: Autoridades de la Nación; Capítulo Cuarto Atribuciones del Congreso,” Honorable Senado de la Nación, accessed July 22, 2011, http://www.senado.gov.ar/web/interes/constitucion/atribuciones.php.

17. "Quilmes Indigenous Community Facing Third Eviction in Three Years," Intercontinental Cry, accessed July 1, 2011, .

18. Miguel Menegazzo Cané, “Potential Restriction on the Acquisition of Rural Land by Foreign Parties,” Buenos Aires Office—Baker & Mckenzie, accessed June 10, 2011,

http://www.bakermckenzie.com/files/Publication/88f5bb4b-195e-4784-b3df-c73f9cdcb653/Presentation/PublicationAttachment/25b56848-e100-4eee-a3eb-c760fdaff8aa/ar_buenosaires_potentialrestrictionsruralland_apr11.pdf.

19. Ibid, Miguel Menegazzo Cané.

20. Negri & Teijeiro Abogados, “Argentina Seeks to Cap Rural Land Ownership by Foreigners,” accessed June 28, 2011.

21. “Mas de un millón de hectáreas en manos de extranjeros,” Bolpress, accessed June 14, 2011, http://www.bolpress.com/art.php?Cod=2011032817.

22. Miguel Urioste, Concentración y extranjerización de la tierra en Bolivia, (La Paz: Fundación TIERRA), 37.

23. Marcos Glauser, Extranjerización del territorio paraguayo, (Asunción: BASE Investigaciones Sociales), 34.

24. “Este año debatiremos sobre la extranjerización de la tierra,” Food Crisis and the Global Land Grab, accessed June 28, 2011, http://farmlandgrab.org/post/view/18208.

25. “Brazil considering leasing farm land to foreigners to circumvent sales restrictions, Merco Press, accessed June 12, 2011, http://en.mercopress.com/2011/05/10/brazil-considering-leasing-farm-land-to-foreigners-to-circumvent-sales-restrictions.

26. Country Profiles of Human Development Indicators: Bolivia (Plurinational State of),” United Nations Development Program, accessed July 6, 2011, http://hdr.undp.org/en/.

27. Oliver De Schutter, “Report submitted by the Special Raporteur on the right to food,” Human Rights Council- Sixteenth Session, (United Nations) 19.

Source: COHA

Nenhum comentário:

Postar um comentário