Bank of England's financial stability report shows that when it comes to central banks borrowing dollars, it pays not to be the Banque de France or the Bank of Japan

Six major central banks were worried enough about the ability of banks to get their hands on US dollars that they stunned the markets yesterday with a plan to make it cheaper and easier to obtain funding in the US currency.

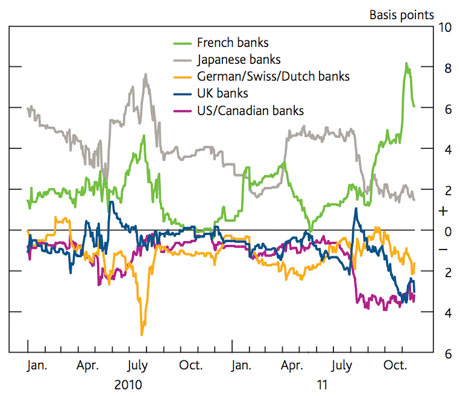

The Bank of England's financial stability report discusses this issue of dollar funding and provides a helpful chart that shows that all banks are not equal when it comes to borrowing dollars.

Dispersion of daily fixing rates for three-month US dollar Libor. Source: Bank of England

Dispersion of daily fixing rates for three-month US dollar Libor. Source: Bank of EnglandThis shows that French and Japanese banks have been paying more for dollars than US, Canadian, UK, German, Swiss and Dutch banks through what is known as three-month dollar Libor (London inter-bank offer rate), which is used as a benchmark for lending rates. The rate is set through quotes provided by a number of so-called panel banks, some of the biggest players in the markets.

The Bank said: "Greater dispersion in fixing rates by panel banks for three-month US dollar Libor also indicated differences in the ability of banks to source US dollars."

Such concerns had prompted additional measures in September 2011 and led to the European Central Bank providing $1.75bn in October and November and the Bank of Japan providing $0.1bn in November. The newest measures do not come into effect until next week.

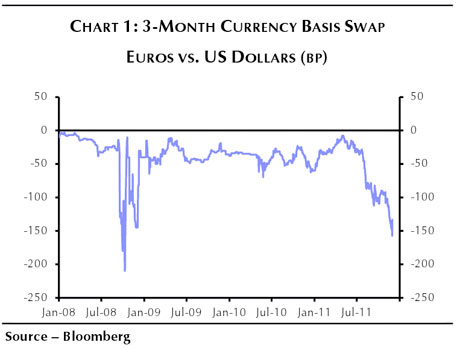

Eurozone crisis: the graph that shows why the central banks had to act

Nervous banks have been charging each other more and more to turn their euros into dollars, creating an incipient liquidity crisis

If there was any doubt about the need for the intervention of the world's central banks to try to avoid a new credit crunch, the chart above tells it all.

Capital Economics explains that eurozone banks have had trouble being able to get funds in dollars, which is why the Bank of England joined the Federal Reserve, the Bank of Japan, the ECB, the Bank of Canada and the Swiss National Bank in taking measures to make it easier for banks to obtain dollars.

The line on the chart is a bit complicated. But Capital Economics explains.

"Until Wednesday, banks were willing to loan euros in exchange for dollars for three months and receive an interest rate of Libor less 150 basis points on the euro, versus paying an interest rate of Libor flat on the dollars. That spread shrunk following the central bank's latest pledge but remained around 130 basis points – far higher than the old rate which banks were prepared to lend dollars".

The upshot is that banks have been charging each other more and more to turn their euros into dollars and that the rates have been reaching levels close to those when Lehman Brothers collapsed in September 2008. Hence central banks decided to act.

But, Capital Economics cautions:

"Welcomed as the news was, we do not think it signals a turning point in the crisis. After all the dollar funding in the eurozone is symptomatic of a broader liquidity squeeze. And even if banks in the eurozone have less of a liquidity problem on their hands today than in they did in late 2008, they have a greater solvency problem".

London: an urban neo-Victorian dystopia

George Osborne's 2011 austerity measures kickstart the inexorable separation of rich and poor

The City of London in 2011 was protected from the Tobin tax. Photograph: Adrian Dennis/AFP/Getty Images

London, once known for its diversity, became progressively more socially and economically segregated after the 2011 austerity measures kicked in, triggering six years of social upheaval that changed the the city forever.

By 2015, academics had coined the phrase "urban neo-Victorian dystopia" to describe the dramatic social and spatial changes in the city they had begun to compare, with only a little exaggeration, with the London described by Charles Dickens 160 years earlier.

The housing benefit reforms of 2012 and 2013 had swept tens of thousands of lower income families out of inner London, to the fringes of the capital and beyond to Margate, Hastings, Milton Keynes and Luton.

This triggered an inexorable and progressive separation of rich and poor in the capital and helped unleash a wave of social problems.

It was boom time for some privileged areas, such as the string of well-to-do neighbourhoods stretching along the north bank of the Thames from Westminster and Notting Hill to Hammersmith that estate agents dubbed the "Golden Westway".

Chelsea, Kensington and Marylebone, once dotted with patches of social housing and deprivation, had become almost almost uniformally gentrified and increasingly sought-after by the wealthier upper middle classes seeking refuge from the day-to-day realities of austerity.

Here, wealthy residents became obsessed with soaring property prices, whether they should exercise their right to privatise the street they lived in, the relative merits of British or Polish private security firms, and the extraordinary difficulty in hiring domestic cooks and cleaners.

By 2017 the last council-owned social housing properties in Westminster were sold under the 2011 right-to-buy scheme. The local authority also annouced the sale of half of its public parks and libraries, Sure Start children's centres and school buildings, for which there was no longer significant public demand – due to the borough's changing economic and demographic profile.

Outside the wealthy centre, things were less serene. Riots sporadically broke out and right-wing bloggers increasingly warned about the suburban menace of unemployed young people. Health officials worried about the tuberculosis epidemic caused by overcrowding in Tower Hamlets. In Barking, the BNP launched a campaign against "Westie scroungers" dispersed from central London in the 2012-13 housing benefit exodus.

A branch of Tesco in Hackney started "austerity days" in 2013, with cheap food offers to coincide with the arrival of weekly benefit payments.

The Salvation Army announced in autumn 2015 that it had just handed out its millionth food parcel, to a family living in Walthamstow.

In 2014, a consortium of housing associations declared that they had converted some empty 2012 Olympic village buildings into temporary "warehouse hostels" for young homeless people.

Criminologists recorded increases in burglary and theft. Social workers pointed out that child protection registers were bulging and psychiatrists noted that prescriptions for anti-depressants had risen exponentially.

Public health officals noted that suicide rates, teenage pregnancies and hospital admissions in poorer areas were rising at five times the London-wide average.

Statisticians argued about whether the number of people who had seemingly "disappeared" from electoral rolls and other official datasets had finally reached the crucial million mark

Announcing the end of austerity in 2017, the government attacked what it called the doom-mongers in the media. Britain had survived its greatest crisis since the second world war by pulling together, the prime minister declared from behind a bulletproof screen outside No 10: "We were, as we have always been, in this together."

North-east England in 2017: still suffering disproportionate damage from austerity

High unemployment, social scars and neglect by Westminster lead to breakaway stirrings in the region's public sector

Middlesbrough is already struggling with high unemployment, feeble economic growth and a shrinking jobs market in 2011. Photograph: Nigel Roddis/Reuters

Middlesbrough's "After the Cuts" special executive meeting in November 2017 was convened to survey the damage caused to the town by the previous six years of austerity, and plot a course for the future.

In common with many other towns and cities in the north-east of England, it had been disproportionately hit by public spending cuts that began in 2011. Already struggling even then with high levels of unemployment, feeble economic growth and a shrinking jobs market, not to mention poverty and poor health, the past half decade had witnessed a progressive worsening in its fortunes.

Once police had removed the noisy protesters from outside the civic centre, the mayor set out a gloomy diagnosis of the town's position. Unlike the rest of the country, Middlesbrough's economic profile was still critically weak. Whereas even recession-hit cities like Manchester had struggled back to 2008 levels of employment earlier that year, Middlesbrough would be relieved if it could reach 1990 employment levels.

Figures presented to the meeting showed that the social fabric of of the town had been badly scarred by austerity.

High unemployment had exacerbated a range of social problems: child poverty, divorce and family break up, alcohol and drug abuse, depression, crime and anti-social behaviour.

Scanning the report in front of him, the mayor picked out a range of other gloomy indicators: the number of 16 year olds going on to further and higher education had plummeted, the town's population had shrunk after 2014 as hundreds of younger people migrated south in search of work.

Middlesbrough had been shocked, he recalled, by the issue of homeless people on the streets, which emerged in the winter of 2013, and the youth riots of summer 2014.

It could all have been a lot worse, he reflected. Tired of being ignored and patronised by a government obsessed with the fortunes of the prosperous south-east of England, in 2014 Middlesbrough had created a shadow north regional government, along with Sunderland, Durham, and Newcastle-upon-Tyne. This body in turn had created a regional investment bank, and lobbied successfully to create a range of "innovation clusters" to drive new industry, including the renewable energy park that had sprung up near Middlesbrough's old container port. The campaign for a dedicated north-east jobs fund in 2015 had been partially successful. Politically, there was a not entirely fanciful discussion of the north-east setting up a fully-fledged devolved government.

But still much remained to be done. The town's legendary resilience and community spirit had been tested, but it was now clearly in need of a little nurturing. The last few years' diminishing public spending budgets in the town had been invested in an ever more desperate attempt to plate over the semipermanent crisis in the NHS, social services and law and order.

There was no money to fix that problem properly. But it was time, the mayor suggested, to make a grand gesture that would show the town was on the mend, and reward its battered inhabitants.

He would announce that Middlesbrough was "renationalising" the town's parks, swimming pools, libraries, museums and leisure centres, sold off to private interests in 2014. This would send a signal that the selfishness and commodification that had pervaded the political sphere over the past five years was over. We'd got too obsessed with the price of everything, he would say, it is time to re-learn what we really value.

Nenhum comentário:

Postar um comentário