For 30 years, poet Simon Armitage's admiration for Morrissey has bordered on the obsessive. But could his love survive an encounter with the famously sharp-tongued singer-songwriter?

It's a bit like being on a date. It's not a blind date exactly; poet meets songwriter seems to be the general idea. But I've no idea if he knows who I am, and for all that I've stalked the man and his music over the years, I can't say with any confidence that I know who Morrissey is either. Can anyone? So when the door opens and he strides into the room, neither of us seems sure of the protocol. I am meeting him of course, that's a given, but is he meeting me? I shake his hand, a square and solid hand, more in keeping with the mobster and bare-knuckle boxer image he's cultivated of late than the stick-thin, knock-me-over-with-a-feather campness of yesteryear. Then he gives a little bow, a modified version of the one I've seen him give about a thousand times on stage, one foot forward and the other behind, head low, eyes to the floor. It's a bit like being greeted by a matador: the gesture of respect is genuine, but we all know what happens to the bull. I cast my eyes downward as well, and notice that he's wearing cute gold trainers, like those football boots reserved for the world's greatest players. They look like they should have wings on the side.

We're in the ballroom of a swanky hotel in a swanky street near London's swankiest department store, and while he's ushered away in the direction of an ornately upholstered chair for a portrait photograph, I head towards the hospitality trolley. Rock'n'roll riders are famously lavish or idiosyncratic, but I am in the company of a man who is famously abstemious. So where there might have been gallons of Jack Daniel's and chopped pharmaceuticals offered on the bare breasts of Filipino slave girls, it comes down to a straight choice between hand-stitched tea bags and several cans of Fanta orange, Morrissey's fizzy drink of choice.

I sidle over to the action. Morrissey is swivelling his head as instructed, registering one pose, then another. The light falls on his rugby-ball chin, then picks out his quiff, somewhat thin these days but still capable of standing a couple of inches above his scalp when given a bit of a finger-massage. He wears a red polo shirt, knuckle-duster rings and the general high-definition radiance of his celebrity. When the camera flashes, there's the occasional glimpse of the younger man within the 51-year-old face, then it fades. Somewhat implausibly in these decorous surroundings, I notice a push-bike leaning against the wall behind the photographer's screen, so I wheel it out and suggest we could do a remake of the This Charming Man video.

"It's been done," he says, with a kind of theatrical dismissal.

I was only kidding.

"Now both of you together," says the photographer.

"Cameron and Clegg," quips Morrissey.

"Which one am I?"

"You're Vince Cable."

The photographer positions us in front of a full-length mirror, not more than three feet apart. It's a me-looking-at-him-looking-at-me-looking-at-him sort of idea.

"Bit closer, please," says the photographer, so I edge a little nearer.

Morrissey: "Am I looking in the mirror?"

Photographer: "Yes, please."

Morrissey: "'Twas ever thus."

Photographer (to me): "A bit closer."

I do what I'm told, until my nose is no further than six inches from his cheek. I can't remember the last time I got within this range of another man's face, and this man is Morrissey, and we've only just met. I notice the grey hairs in his sideburns, his indoor complexion, the cool quartz of his eyes. I inhale the atomised confection of what I assume is an expensive cologne.

For me, this close encounter could be described as the arrival point of a journey that started over a quarter of a century ago. I won't go into the exact circumstances, except to say I was lying in a bath in a house on the south coast of England shared with five geography students and several members of the Nigerian navy. On the windowsill was a battery-operated transistor radio, and out of its tinny speaker, John Peel was talking about a band called the Smiths. Peel was never one for hype or eulogy, but somewhere within the lugubrious voice and deadpan delivery, I thought I heard a little note of excitement and perhaps even an adjective of praise. I dipped below the waterline to rinse the last of the Fairy Liquid out of my hair, and once the water had drained from my ears, I found myself listening to Hand In Glove. And to a homesick northerner honed on alternative guitar music, it was love at first hearing: everything came together with the Smiths, a band whose very name suggested both the everyman nature of their attitude and the fashioned, crafted nature of their output. When Morrissey sported Jack Duckworth-style prescription glasses mended with Elastoplast I went looking for a pair in the market. When he wore blouses and beads, I waited until my mother had gone to a parochial church council meeting then had a flick through her wardrobe and jewellery box. And once he had appeared on Top Of The Pops with a bunch of gladioli rammed in his back pocket, any garden or allotment became a collection point on the way to the disco, and the dance floor, come the end of the night, would look like the aftermath of the Chelsea Flower Show. The Smiths split up in 1987 but Morrissey threw himself into a solo career, going on to produce – in my estimation – an unrivalled body of work, one that confirms him as the pre-eminent singer-songwriter of his generation. I listen to the albums ceaselessly. Despite which, I have never particularly wanted to meet Morrissey. A high court judge famously branded him as "devious, truculent and unreliable", and in interviews he has always appeared diffident, a touch arrogant and always uncomfortable. In fact, I've always wondered why someone who seems so painfully awkward in the company of others would want to punish himself with the agonies of public performance?

"Because as a very small child I found recorded noise and the solitary singer beneath the spotlight so dramatic and so brave… walking the plank… willingly… It was sink or swim. The very notion of standing there, alone, I found beautiful. It makes you extremely vulnerable, but everything taking place in the hall is down to you. That's an incredible strength, especially for someone who had always felt insignificant and disregarded. Coupled with the fact that you could also be assassinated…"

We're now sitting in diagonally positioned chairs with a table between us, Morrissey with his stockpile of Fanta, me with my list of questions.

"Where's home?"

"I'm very comfortable in three or four places. When the world was a smaller place, Manchester was the boundary. But it's a relief to feel relaxed in more places than just one. I know LA well, but it's a police state. I frequent Rome and a certain part of Switzerland. And I know this city very well."

"And presumably it would be a problem now, walking down Deansgate. Because of the fame?"

"Yes, but I don't really do all the things that famous people do."

"You don't dip your bread in, you mean?"

"Yes. That's very well put. I can see why Faber jumped on you."

It's quickly apparent that Morrissey's wit, articulacy and all-round smartness is always going to mark him out as an oddity in the music business. It's also clear that the sharpness of his tongue will make him more enemies than friends, and his list of dislikes is long. Morrissey on other singers: "They have two or three melodies and they repeat them ad nauseum over the course of 28 albums." Morrissey on people: "They are problems." And on the charts: "Nothing any more to do with talent or gift or cleverness or originality. Every new artist flies in at number one, but in terms of live music they couldn't fill a telephone box." And shockingly, on the Chinese: "Did you see the thing on the news about their treatment of animals and animal welfare? Absolutely horrific. You can't help but feel that the Chinese are a subspecies." Neither is he impressed with Arctic Monkeys' Alex Turner ("an NME creation") or George Alagiah (an unspecified complaint signalled with a roll of the eyes), and his views on the royal family would have seen him hanged in former times. He even has a low opinion of our poet laureate, and when I refuse to be drawn into the sniping, pointing out that she happens to be a friend of mine, this seems to encourage his desire to disparage. Like many who've gone before me, as the conversation rolls on I find I can't unpick the contradictions. The charm, but also the barbed comments. The effeminate gestures, then the surly machismo. The desire to be centre stage coupled with the lack of social ease. The obvious trappings of success, fame and fortune, but the repeated complaints of victimisation and neglect. What I am certain of is that nobody is more aware of being in the company of Morrissey than Morrissey himself. Call it self-consciousness, call it self-absorption, call it self-defence, but every gesture seems carefully designed, and every syllable weighed and measured for the ripples it will produce when lobbed into the pond. Sometimes it's in the form of a brilliant, Wildean retort, sometimes it's a self-deprecating comment of suicidal intensity, sometimes it's a shameless remark about the indisputable nature of his own brilliance, and sometimes it's a claim so mystifying that at first I think he's taking the piss.

"I'm cursed with the gift of foresight," he says. Then a few minutes later, he says it again.

"You don't mean in a crystal ball kind of way, do you?"

"That's exactly what I mean. Cross my palm with silver."

I smile at the thought of one of life's renowned social realists staring into the tea leaves, and I'm on the point of asking him to prove his assertion by forecasting the winner of this afternoon's 3.30 at Market Rasen when I notice he isn't joking.

"Do you find that you've accumulated cash?" he asks me, apropos of nothing.

"I get by."

"Is that a way of saying you've got loads but you're too embarrassed to admit it?"

"How would you like it if I asked you how much you earned?"

"Not an answer."

"I earn more than I thought I would when I became a poet."

"When did you know you were a poet?"

"Not until other people said I was."

Referring to his own experience, he tells me, "Once you feel it and other people feel it, too, you stand and are authorised as a poet. I was the boy least likely to, in many ways. I was staunchly antisocial. It was a question of being a poet at the expense of being anything else, and that includes physical relationships, strong bonds with people. I think you discover you are a poet; someone doesn't walk up to you, tap you on the shoulder and say, 'Excuse me, you are a poet.' "

In fact, Morrissey isn't a poet. He's a very witty emailer ("Bring me several yards of heavy rope and a small stool," he wrote, when I'd asked him if he'd like anything fetching from the north), and a convincing correspondent, especially on the subject of bearskin hats, as his recentletter to the Times testified ("There is no sanity in making life difficult for the Canadian brown bear, especially for guards' hats that look absurd in the first place"). He has also penned an autobiography, which he assures me is "almost concluded". But poets write poems, requiring no backbeat, no melody, and no performance. Being the author of There Is A Light That Never Goes Out and other such works of genius doesn't make him WH Auden, any more than singing in a band called the Scaremongers at weekends makes me an Elvis Presley.

"Are you a violent person?" I ask. "You flirt with violent images in your work. Guns, knives…"

"All useful implements. As you must know, living where you live. Do you go out much, into those Leeds side streets?"

"No."

"You're missing everything."

I say, "At this moment in time you have no contractual obligations, do you?"

"That's right."

"I thought labels would be queuing to sign you."

"Believe me, there is no queue." Surprisingly, a rant about the music industry develops into a very touching statement about his band, talking almost paternalistically about his responsibilities and loyalties. The tone of voice reminds me of a recent email he posted to a Mozzer website, a tender and poignant citation for a girl who wasn't much more than a regular face in the crowd at his concerts, but whose devotion and death had clearly touched him. In fact, he talks movingly about all his fans, as if they were blood relatives, or even something more intimate. Which, rightly or wrongly, I take as my cue to ask him about his love life, or his alleged celibacy. Not because I want to know if he's gay or bi or straight, but because I can't understand how a man who apparently shuns emotional involvement and physical proximity of any kind can write with such passion and desire. If it isn't personal, is he simply making it all up?

"Well, it is personal because I have written it. But I don't believe you need to be stuck in the cut and thrust of flesh-and-blood relationships to understand them. Because if that was the case, everyone on the planet who had been married or in a relationship would be a prophet of some kind, and they're not. You don't need to be immersed to understand. And if you do take on a relationship you have to take on another person's family and friends and it's… really too much. I'd rather not. You find yourself working overtime at a factory to buy a present for a niece you can't stand. That's what happens when you become entangled with other people."

"But aren't you lonely?"

"We're all lonely, but I'd rather be lonely by myself than with a long list of duties and obligations. I think that's why people kill themselves, really. Or at least that's why they think, 'Thank heaven for death.' "

"How would you describe your level of contentment?"

He muses on the question for a moment. "Even."

"Does that mean your writing is a cold and clinical activity?"

"No, never clinical. I feel I don't have any choice. It's constant and overpowering. It has to happen. Even at the expense of anything else. Relentless. I know it's… insanity. An illness in a way, one you can't shake off."

"Will you keep on doing this till you fall over, or will there come a time when you decide to pack it in and paint pictures or plant an orchard instead?"

"The ageing process isn't terribly pretty… and you don't want yourself splattered all over the place if you look pitiful. You can't go on for ever, and those that do really shouldn't."

"Any names?"

"No names. Why mock the elderly?"

While trying not to lose eye contact, I glance at the list of remaining questions in my notebook.

"Do you own a valid driving licence?"

"What kind of bland, insipid question is that?"

"It's a good question, isn't it? Has anyone asked you it before?"

"No. But that's hardly a surprise, is it?"

"I thought it was a beauty."

"Why? Because you consider me incapable of operating such large and complex pieces of engineering?"

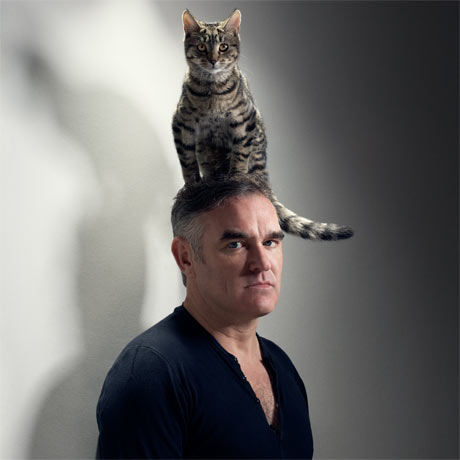

"OK, how about, 'Do you have any pets?'"

"Yes. Cats. I've had lots of cats. But also many bereavements."

A prescient remark, as it turns out, and one that suggests I should have taken Morrissey's powers of prediction more seriously. Because a week or so later I get a message to say he hates the photographs so much he has insisted they will never see the light of day. The bereavement, it seems, is mine, in the sense that he won't be seen dead with me. And I am to be replaced in the images by a cat. Thirty years of admiration bordering on the obsessive, then a date, then dumped. Jilted for a fucking moggy.

Back at the hotel, he doesn't seem to be in any sort of hurry, but the conversation has run its course, and as a way of winding things up I embark on some ill-conceived sentence that begins as a heartfelt compliment but escalates into some lavish toast of gratitude on behalf of the nation. With no obvious end to the burgeoning tribute in sight, I cut to the chase and simply say thank you.

"And I have a little gift for you," I add, pulling my latest slim volume out of my bag.

"Will you write something in it?"

"I already did."

"Two r's and two s's," he says. And I think, don't worry, Morrissey; if anyone knows how to spell your name, it's me.

He spins around on the thick carpet and walks towards the staircase. Except half way down the corridor he opens the book of poems and pulls out – forgive me, people, but who wouldn't have? – a Scaremongers CD.

"Did you know you'd left this in here?" he asks.

"Er, sort of," I admit.

His eyebrows lift and fall, uncomprehendingly. Then the little wings on his golden shoes flutter about his ankles, and he ascends into heaven. •

• Everyday Is Like Sunday is rereleased on 27 September, and Bona Drag on 4 October.

Nenhum comentário:

Postar um comentário